Many of the key markers of an inflation-driven bear market bottom are still missing today— little real economic weakening, few signs the central bank is ready to move to easing, and, as of yet, not much repricing of equities beyond the direct drag from rising interest rates.

Global equity markets are down more than 17% this year as central banks responded to strong inflation with a record pace of tightening. Have stocks fallen enough to see the bottom in the market, or is more pain ahead? One perspective we have found helpful when considering this question is comparing conditions today to past inflation-driven equity market bottoms.

Bear markets typically unfold in a sequence: 1) rising interest rates push down equity prices, as any future cash flow is discounted to the present at a higher yield; 2) higher rates and growing economic uncertainty draw money out of risky assets, depressing equity prices further as risk premiums rise; and 3) the combination of the impact of rising discount rates, risk premiums, and declining asset prices leads to declining economic activity and earnings, creating more downward pressure on equities.

The equity bottom typically does not come until 1) there is a meaningful period of easing sufficient to offset the negative economic momentum, and 2) equity prices fall enough that investors are incentivized to move back out the risk curve and buy stocks. The former typically means that central banks assess that the slowdown in economic activity has been large enough to bring inflation back under control. And the latter means equities typically decline much more than justified by higher interest rates, resulting in valuations that are low enough to draw investors back in.

When we look at conditions today, the typical markers of an equity market bottom are not yet present. Inflation remains very high, and the economy remains relatively strong, such that a Fed easing does not seem likely (currently the Fed has only indicated that it will slow its tightening). And despite the drop in equity prices, long-term equity expected returns still look poor compared to bonds and cash—meaning investors still lack a strong incentive to jump back in. The Fed will likely need to see more weakness—and investors, lower prices—before equities find a floor and begin a sustainable climb.

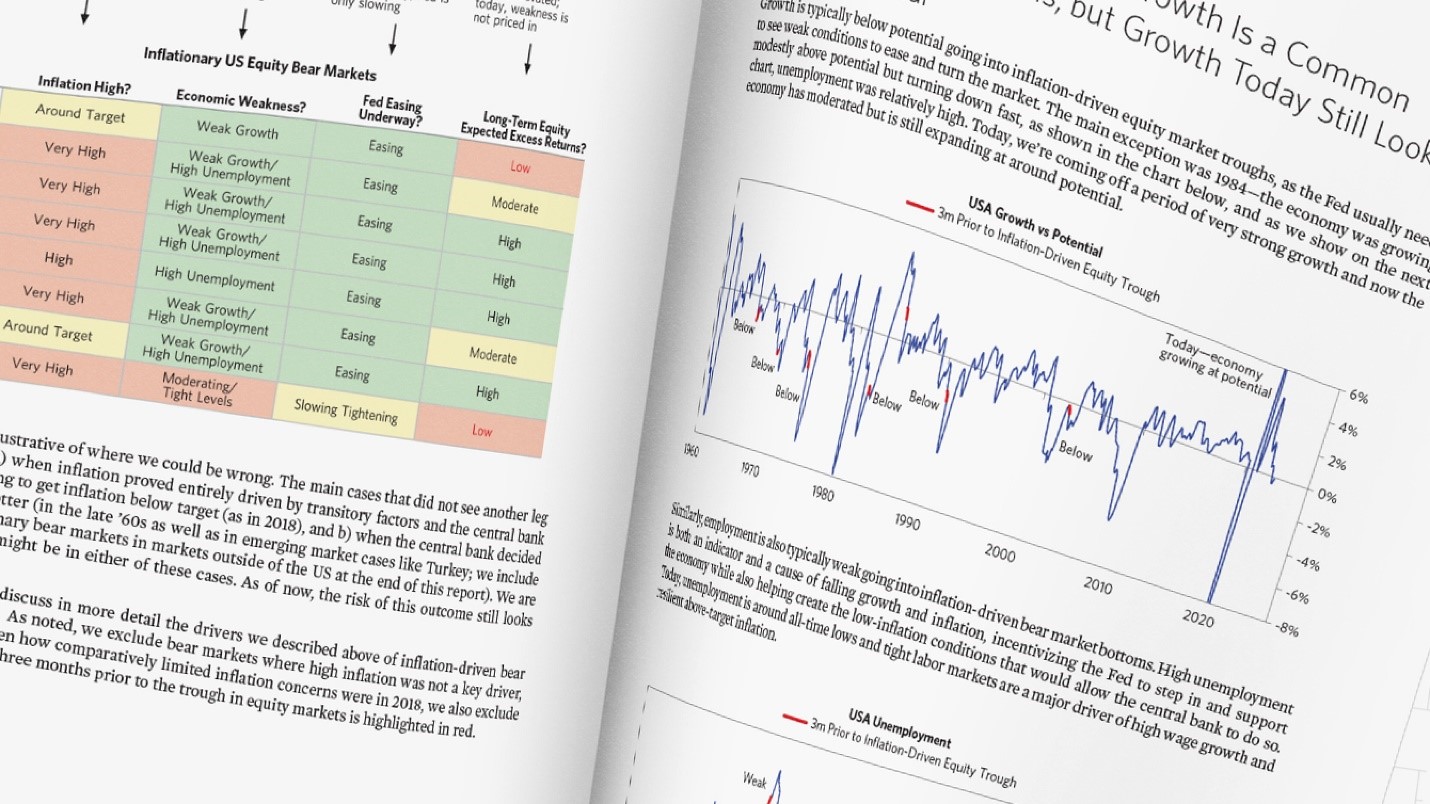

The table below synthesizes economic conditions and equity pricing around inflation-driven bear market troughs in the US (i.e., cases where concerns around high inflation drove Fed tightening that led to the equity sell-off). Inflation is typically a lagging indicator; equities rallies have typically begun when inflation is still high. Instead, rallies begin when central banks see meaningful economic weakness and shift into gear to ease to stop the downturn and when equity markets have gone through a meaningful repricing.

Equity Bottoms Are Typically Accompanied by Inflation Turning Over; Today, Inflation Has Moderated, but Under the Hood, Wage Growth Has Picked Up the Baton

While inflation is still high, it has come down from its peak over the past few months. In a number of the inflationary historical bear market cases, equities turned up just as inflation turned down from highs and discount rates fell. Across the historical cases, however, the turn in inflation was accompanied by meaningful economic weakness that required the Fed to choose between inflation and economic pain. And as discussed, this weaker growth and high unemployment was itself an ongoing downward pressure on inflation.

Today, moderating inflation is not accompanied by weaker growth and inflation seems unlikely to hit central bank targets any time soon. As some of the commodity surges and acute supply chain challenges roll off, wage growth (running north of 5%) is picking up the baton and fueling the next leg of inflation. As a result, the Fed is not yet being forced to choose between weak growth and high inflation and is still able to concentrate primarily on its inflation mandate. It’s also worth noting that the Fed is already discounted to slow its pace of tightening, so any support to equities will need to come from the Fed easing more than what is already discounted.

Equity Bottoms Are Typically Accompanied by a Significant Period of Easing; Today, the Fed Has Yet to Pause

Today, the Fed has stated that it might consider slowing its future pace of tightening. Typically, it takes much more than this to bring about the bottom in the equity market. It takes a long enough period and significant enough amount of easing to really offset economic weakness and bring about an upturn. The chart below shows this point. Note the format is a bit different from those shown above. We show equity market drawdowns, but this time the line in red illustrates the period when the Fed was actively easing. This highlights that the most significant drawdowns in US history have occurred after the Fed shifts to lowering rates.

While we mainly focus on the US in this report, a similar pattern holds true in inflationary equity bear markets across other developed economies and emerging markets. There is a collection of cases where EM central banks eased fast enough and hard enough to offset a cash flow decline prior to any real weakening in employment (Turkey throughout the 2000s and Brazil in 2012). In these cases, ultimately, the central bank was really letting inflation go. Note this analysis excludes hyperinflation cases.

We also hold a slight bias for credits in the U.S. market versus Europe. From the ongoing war in Ukraine to the softness in the housing market, risks are more elevated in Europe than in the U.S., which could result in a greater impact on consumer sentiment and spending and therefore a more severe or prolonged recession.

Focusing on the Long Term

Looking ahead, a potential recession, ongoing inflationary pressures, hawkish central banks policy and earnings volatility will certainly remain front and center. In this environment, and with markets likely to remain volatile in the coming months, investors do not need to take on excessive risk to earn potentially attractive returns. In higher-rated parts of the bond and loan universe, as well as in certain parts of the CLO market, the risk-reward picture remains compelling. However, a credit-intensive approach is crucial—to not only avoiding additional downside, but also identifying issuers that can withstand today’s headwinds.